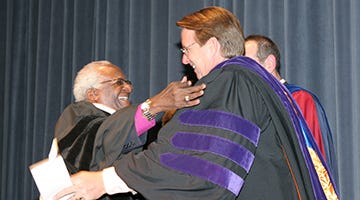

x Archbishop Tutu greeted by then-President John Delaney before delivering the President’s Address at UNF in 2003 (Credit: UNF Website)

This first blog of 2022 reflects on two rituals, one in Atlanta in 1986 celebrating the first Martin Luther King Day; the other here in Jacksonville in 2008 celebrated the work of Rev. Edward Harrison, former Dean of St. John’s Cathedral.

The two events are tied together by the sacred thread of reconciliation and racial healing.

Rituals that uplift and heal

Rituals are always rich with meaning. They help us to define what’s important in our culture.

When it comes to divisions in our country, rituals carry special significance. The racial disparities that tear at the fabric of our nation are often carried in rituals of mourning and grief.

The source of this mourning and grief? Ritual killings of black men, women and children in our streets. Rituals of confrontation and conflict. Unacknowledged rituals of suffering among Black women whose babies die disproportionately before their first birthday. Unacknowledged rituals of dislocation as black men walk through prison doors, unjustly held. We’ve become numb to these events of unacknowledged grief and mourning.

These are not random incidents; unfortunately, they rise to the level of cultural rituals that were originally created to terrorize and control, and to justify a system of greed, dominance and racism.

Now we need to create new rituals, ones that acknowledge the truth, elevate the souls we lost and expand the process of racial healing. This includes rituals of repentance, atonement, apology and forgiveness that redefine our social ethics and create a new moral order.

Such rituals will take us beyond our difficult past in order to discover the underlying wholeness that is inherent in the human condition: We are one people.

Ritual #1 --- Ebenezer Baptist Church, January 1986

Archbishop Tutu welcomed by Coretta Scott King - First King Day Holiday (AP Photo)

The first national holiday in celebration of Dr. Martin Luther King was held in January of 1986, 36 years ago this month.

Among the uplifting rituals of celebration that first King Day was the one at Ebenezer Baptist Church, Dr. King’s home church in Atlanta. Ebenezer was the base of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. That celebration culminated an 18-year campaign to elevate King’s birthday to the status of a National Holiday.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu

The man who stood in the pulpit to preach at Dr. King’s church that day was Archbishop Desmond Tutu. His death on Dec. 26th, 2021, three weeks before this year’s King Day rituals, highlights this memory.

Archbishop Tutu had been invited to speak by the King Family --- a high honor. He was also there to receive the first Martin Luther King Peace Prize, established by the King Family following Dr. King’s assassination.

Coretta Scott King and her children were present. The pews were jammed with people who had participated in struggles for peace and justice all across this country and around the world.

As with all rituals there, the ceremony at Ebenezer was rich with meaning. Here was one Nobel Peace Prize winner preaching in honor of another. Here was a hero of the South African anti-apartheid movement preaching in honor of the American hero whose movement for racial justice here inspired the freedom movement in South Africa.

“Like Martin, Bishop Tutu possesses faith that dissipates despair,” Ms. King said as she presented the award to Archbishop Tutu. “Like Martin, he repeatedly encourages those who are denied fundamental human, civil and political rights never to doubt that they will one day be free. Like Martin, Bishop Tutu understands that injustice enslaves the oppressor and the oppressed. Like Martin, he works and lives through a belief in the inevitability of liberation and justice.”

In accepting the award, Archbishop Tutu extolled the shared commitment to reconciliation in the U.S. Civil Rights Movement and the South African anti-apartheid movement.

“To side with us is to side with justice, to side with peace, to side with righteousness, to side with reconciliation, to side with compassion, to side with sharing, to side with caring,” he said.

“It is a very great honor that has been bestowed upon me, and I tremble as I stand in the shadow of so great a person.”

He noted that the Civil Rights Movement and the anti-apartheid movement were both guided by Dr. King’s philosophy of nonviolence. Black people in both countries had been “peace-loving to a fault” in their struggles for freedom, he noted.

Rituals Elevate Vision

Uplifting rituals have a way of elevating our vision, of moving us from ego and self-interest to realms of spiritual and moral values.

This pursuit of higher human values and common ground is not easy. Both Dr. King and Archbishop Tutu suffered because of their commitment to peacemaking. Dr. King was critized by young activists and ultimately paid with his life. Archbishop Tutu was condemned by young revolutionaries in South African for forgiving whites who had played a role in the slaughter of Blacks during apartheid.

His commission was derided as “The Handkerchief Commission” when he and others wept openly hearing stories of suffering and pain by Blacks and Whites alike who testified.

His response was characteristic of the man, his spirit and his values. It also set the tone for rituals of reconciliation.

“I listen to every single story: They are all the same and they are all unique. In those hearings, I saw the very worst that humans are capable of and I saw the very best of what we humans are capable of.”

Sen. Edward Kennedy acknowledged the connection between Dr. King’s legacy and that of Archbishop Tutu, referring to the Archbishop as “the Martin Luther King of South Africa.”

Ritual #2 – St. John’s Cathedral, Jacksonville - December, 2008

Rev. Edward Harrison, Dean of St John’s Cathedral - 2008

Twenty-two years later, in December of 2008, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, was in another church to participate in another ritual --- a celebration that was also connected to racial reconciliation.

Several hundred people gathered at St. John’s Cathedral in downtown Jacksonville to celebrate the departure of Rev. Edward Harrison, Dean of the Cathedral for eight years who was leaving for a new assignment at a church in San Diego.

As parishoners gathered in the church’s function hall that evening, the doors swung open and in walked a smiling, jaunty Archbishop Tutu. The crowd gasped in surprise and awe, then applause. Archbishop Tutu had attended St. John’s in 2003 and 2004 and occassionally preached from its pulpit. It was his home church in Jacksonville while he served as a visiting lecturer at the University of North Florida at the invitation of then-President John Delaney and Oupa Seane, Director of the UNF Intercultural Center for PEACE. Seane, who spent a year in prison in South Africa for opposition to the apartheid government, is a longtime friend of Archbishop Tutu.

Archbishop Tutu’s return for Rev. Harrison’s farewell raised the event to another level.

“I was totally surprised that day,” Rev. Harrison told me recently. Retired from the clergy, he and his wife Teresa have returned to live in Jacksonville. I reached him at his home.

“I couldn’t believe the Archbishop would fly in to be at my going away party. He was revered around the world and here he was showing up for a local pastor in Jacksonville, Florida. He was a powerful presence at the Cathedral in those years. His Palm Sunday sermons were always special. It still leaves me humbled and amazed that he flew in for my event,” Rev. Harrison recalls.

The St. John’s Cathedral Truth & Reconciliation Community

St. John’s Cathedral Truth & Reconciliation Community Retreat at Marywood Conference Center

Among those present at the celebration were members of the Church’s Truth & Reconciliation Community. This group of 16 parish members had come to understand the power Archbishop Tutu’s philosophy and the significance of rituals of racial reconciliation.

The group was founded by Rev. Harrison modeled on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa created by President Nelson Mandela and Archbishop Tutu, who decided it was better to forgive those who had oppressed Blacks than to punish them.

Rev. Harrison based the St. John’s Truth & Reconciliation process on the ritual hearings of the South African commission, which was chaired by the Archbishop.

“When Archbishop Tutu came to the cathedral, my interactions with him made me think we needed to have some kind of platform for racial reconciliation in Jacksonville. Grievances and issues in our town could be surfaced in the spirit of true listening and addressed with respect,” Rev. Harrison said.

“The Archbishop had created something in South Africa we could use as an example here in Jacksonville. His Commission did not mete out prison sentences or judgements. Its whole impetus was to get the truth out to allow for the healing that happens when people tell those truths.

“You have to have truth-telling in order to have reconciliation. You can’t have reconciliation without acknowledging the truth. So, we offered ourselves as a spiritual community in order to live it in our own beings.”

Personal and group transformation

Over the course of two years, the St. John’s Truth & Reconciliation Community built a unique process with practices and rituals that, in the words of Rev. Harrison, “transformed the individuals and rippled out into our Vestry and the surrounding community.” St. John’s began to see itself as “the church in the heart of the city with the city in its heart.”

The Truth & Reconciliation Community included some conservative members of the church as well as some liberal ones, blacks and whites, men and women, people who were gays and people who were straight, Rev. Harrison recalls.

While it was modelled on the South African Commission “we discovered our own version of truth and reconciliation, one that suited us,” Rev. Harrison recalls.

As facilitators, Shirley and I were part of that community. We were blessed with several opportunities to sit with Archbishop Tutu in private conversation. He was thrilled that St. John’s had taken on the project and was fully and supportive of its efforts. In person he was a light-hearted, yet intense man who exuded a peaceful spirit. He shared what worked and what didn’t work in South Africa’s efforts openly with us.

“But you have to find your own way,” he told us.

The Power of Ritual

The work of St. John’s Truth & Reconciliation Community was characterized by many rituals.

Among them was recognition at the annual Episcopal Diocesan Convention of 2009 when the value of the Community’s work was formally acknowledged by Convention members with the blessing of the Bishop --- a high honor.

To get to that point the TRC, as it was known, engaged in deep dialogue and interaction.

Its first ritual was a two-day retreat at Marywood Conference Center in St. John County.

“The Marywood Retreat was transformative for people,” Rev. Harrison recalls. “We’d become so accustomed to our own rhetoric, our preconceptions. At Marywood we got to a different space with each other. We walked the grounds together down by river. We reflected. We shared our stories. We had time to process.

“We looked deeply into ourselves and shared aspects of our lives we had never talked about before about our experiences of racism, growing up white or black, male or female, gay or straight. The group became a community as people experienced how meaningful it was to engage in safe, respectful conversations.

“This is a moral crisis we’re in today,” he added. “Our politics has become our new religion. If we’re going to become a global community in a peaceful world, we have to learn that the collective matters as much as the individual. We have to learn to relate as spiritual beings where we forego our own predispositions, stop being reactive and become more self-reflective as a country, yes much more thoughtful and reflective together as a people.”

The specific work of the Truth & Reconciliation Community remains private to the group. The themes that emerged were shared openly, while personal stories were held sacred and confidential.

Activities that brought the group together became emotional experiences that rose to ritual, taking on deeper meaning.

A Ritual of Reconciliation

These experiences included a Liturgy of Reconciliation.

In Christian churches, liturgy is a form of public expression giving voice to a set of principles or ideas. All religions capture their principal beliefs in one form or another. Some liturgical expression, therefore, has universal meaning across all systems of belief. For example, spiritual expressions across all cultures carry a belief in the power of love.

The Liturgy of Reconciliation allowed members of the Truth & Reconciliation Community to distill their work together into a simple, elegant statement spoken aloud across the room, person-to-person.

That statement included the main elements of reconciliation:

Truth-telling through stories

Acknowledgement

Apology

Repentance

Forgiveness

Atonement

These qualities were central to the beliefs of Dr. King and Rev. Tutu. They imply rituals of great meaning. For individuals to repent, forgive and atone involves a change of heart and a new quality of relationship. The healing begins.

A Personal Note

As a Black man who has experienced American racism, I understand the challenge of forgiving. Many have suggested that forgiveness cannot come until there are reparations, for example. However, in my life true forgiveness is without such preconditions. Ultimately, it is about my inner peace, not the perpetrator.

I find relief whenever I forgive myself for holding onto resentment and anger. This relief opens space in my heart to bear witness to the story of the person whose words or deed inflicted hurt or pain on me. The healing begins with empathy.

Clearing the space

Whenever I participate in an uplifting ritual I experience relief, clearing negative energies that derive from racial legacies. Clearing negative energy creates the space for reconciliation.

Engaging in uplifting rituals clears out emotions that separate me from others and helps me rise above my stereotypes and preconceptions. This is a daily practice; I remain a work in progress, every day, every moment.

I’ve written elsewhere my belief that Black people are paying a very high a price for holding onto our resentment and anger. And, I believe white people --- and our nation as a whole --- are paying a very high price for not acknowledging “the sins of the past.” We all remain profoundly entangled in this interconnected culture that enabled centuries of slavery and oppression.

When we approach racial reconciliation in a spirit of true collaboration, our work takes on deeper meaning. As we elevate the work of racial healing into realms of ritual, we discover new ways to sustain movement forward in the work.

Each of us carries that divine spark, that divine potential. Collectively, we are capable of greater humanity than our behaviors often suggest.

What better way to honor the legacies of Dr. King and Archbishop Tutu, and the rituals of love, repentance and forgiveness they espoused?

Thanks for subscribing. This post is public, so feel free to share it.

Thank you for sharing these important experiences and thoughts. The energy they carried forward continues in us. The energy that uplifts always meets the challenges of the energies that pull down. We aim for balance.

Thank you Bryant for this eloquent post celebrating both ritual and ascended Archbishop Desmond Tutu. This was a hope the former organization NCCJ (now One Jax) had in 1999 when we helped organize the 40th observance of Ax Handle Saturday. This day languished in obscurity, when Rodney Hurst and Alton Yates approached several organizations with the hope that recognition of this day would spark healing and constructive dialogue. Ritual is powerful, prompting self introspection and safe space for sharing different points of view. Thank you again for this powerful message.